Overview

FY 2021 Budget Request

LSC requests an appropriation of $652,600,000 for FY 2021. This request reflects an increase of $59.6 million over last year’s request of $593 million. Nearly 95% of the request would fund 132 local legal aid organizations in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Territories. LSC estimates that this would enable LSC grantees to provide assistance with 60% more civil legal problems than they currently serve.

Last year, LSC used its 2017 Justice Gap Report as the basis for determining the level of funding necessary to narrow the justice gap. LSC’s FY 2021 recommendation is based on a new “intake census” of all LSC grantees that focused on financially eligible individuals who sought assistance for civil legal problems during a four-week period in 2019. The 2019 intake census showed that 42% of the eligible legal problems presented received no service of any kind—an increase of one percentage point from the 2017 survey.

LSC’s funding request for FY 2021 reflects the overwhelming need for civil legal services to fulfill America’s pledge of “justice for all.” Millions of Americans qualify for LSC-funded services, but the majority of them are not able to receive the legal assistance they need because LSC’s appropriation has been inadequate to meet their needs. The request would allow LSC grantees to make substantial progress serving those persons who seek legal aid but currently receive insufficient services or no service at all.

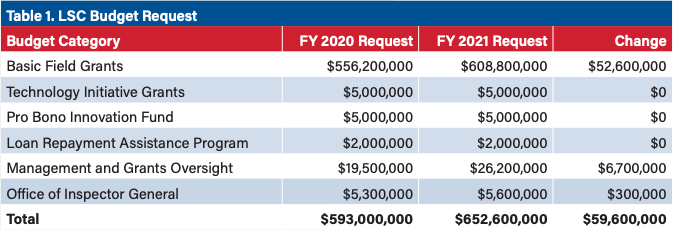

The table below compares LSC’s request by budget category for FYs 2020 and 2021. Basic field grants, which support the day-to-day operations of LSC-funded civil legal aid programs, represent the largest component of LSC’s budget request. For FY 2021, LSC requests $608.8 million for Basic Field Grants to narrow the “Justice Gap” as measured by the percentage of eligible legal problems LSC’s grantees must turn away with no help of any kind.

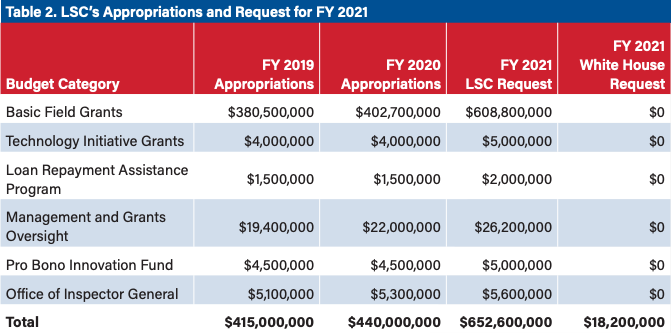

In December 2019, Congress enacted FY 2020 omnibus appropriations legislation that funds LSC at $440 million, a $25 million increase from FY 2019. This represents a six percent increase from last year.

The White House continues to call for the elimination of funding for LSC. In its FY 2021 budget request to Congress, the administration recommends $18.2 million for LSC for closure of the Corporation. LSC has strong bipartisan support for robust funding among Members of Congress and external stakeholders. Last year, 209 members of the House of Representatives signed a bipartisan letter in support of funding for LSC, the largest number in history, and 46 bipartisan Senators signed a similar letter in support of funding for LSC. Members of the legal and business communities, state attorneys general, and law school deans across the country sent letters to the House and Senate appropriations committees advocating for increased funding for LSC. They included:

- 252 General Counsels from some of the nation’s largest corporations, including Apple, American Express, Google, Walmart, General Motors, and Walt Disney.

- 181 law firms from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

- The Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators.

- 41 bipartisan state Attorneys General.

- 167 Deans of law schools, 80% of all ABA approved law schools in the U.S.

The table below reflects LSC’s current funding compared to LSC’s and the White House request for FY 2021.

Eligible Population and LSC Funding

An estimated 57.3 million people, or 17.8% of the U.S. population, were eligible for LSC-funded services in 2018, the most recent year for which Census Bureau figures are available. The eligibility standard is 125% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines. The following map illustrates the geographic location of the population eligible for LSC-funded services across the United States in 2018.

LSC’s congressional appropriation represented 34% of the total funding LSC grantees received in 2018, the most recent year for which LSC currently has grantee reports. LSC’s appropriation today is far lower in inflation-adjusted dollars than it was forty years ago. If LSC’s funding in 1980 had kept up with inflation, its funding today would be $879 million.

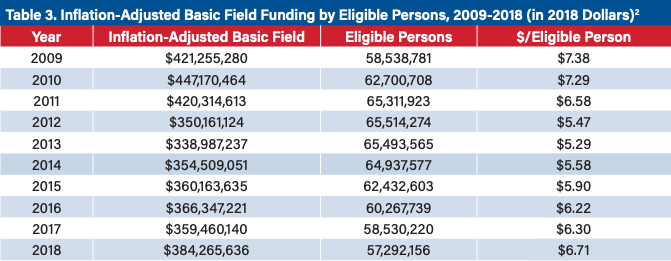

The table below shows LSC funding per eligible persons in inflation-adjusted dollars from 2009 to 2018. In 2010, basic field funding of $447 million in inflation-adjusted dollars amounted to $7.29 per eligible person. Eight years later, Basic Field Funding was only $6.71 per eligible person in inflation-adjusted dollars.

LSC grantees leverage the funding they receive from our congressional appropriation with private contributions and state and local funding. Thirty-four grantees received 50% or more of their total funding from LSC in 2018. The following map shows the percentage of Basic Field funding that grantees in each state received from LSC in 2018.

The "Justice Gap" Continues

Last year, LSC used its 2017 Justice Gap Report as the basis for determining the level of basic field funding necessary to narrow the justice gap. LSC’s FY 2021 recommendation is based on a new intake census of all LSC grantees that focused on financially eligible individuals who sought assistance for civil legal problems during a four-week period in March and April of 2019. The 2019 census showed that:

- 42% of the eligible legal problems presented received no service of any kind—an increase of one percentage point from the 2017 survey.

- Only 27% percent of eligible problems presented were fully served.

- 17% received some service, but not full service.

- 13.5% received service, but the extent of service was pending at the time of the census.

If Congress fully funds LSC’s request of $608.8 million for Basic Field grants, LSC grantees could provide some level of service for 60% more civil legal problems than they currently serve.

Washington State Legal Needs Study

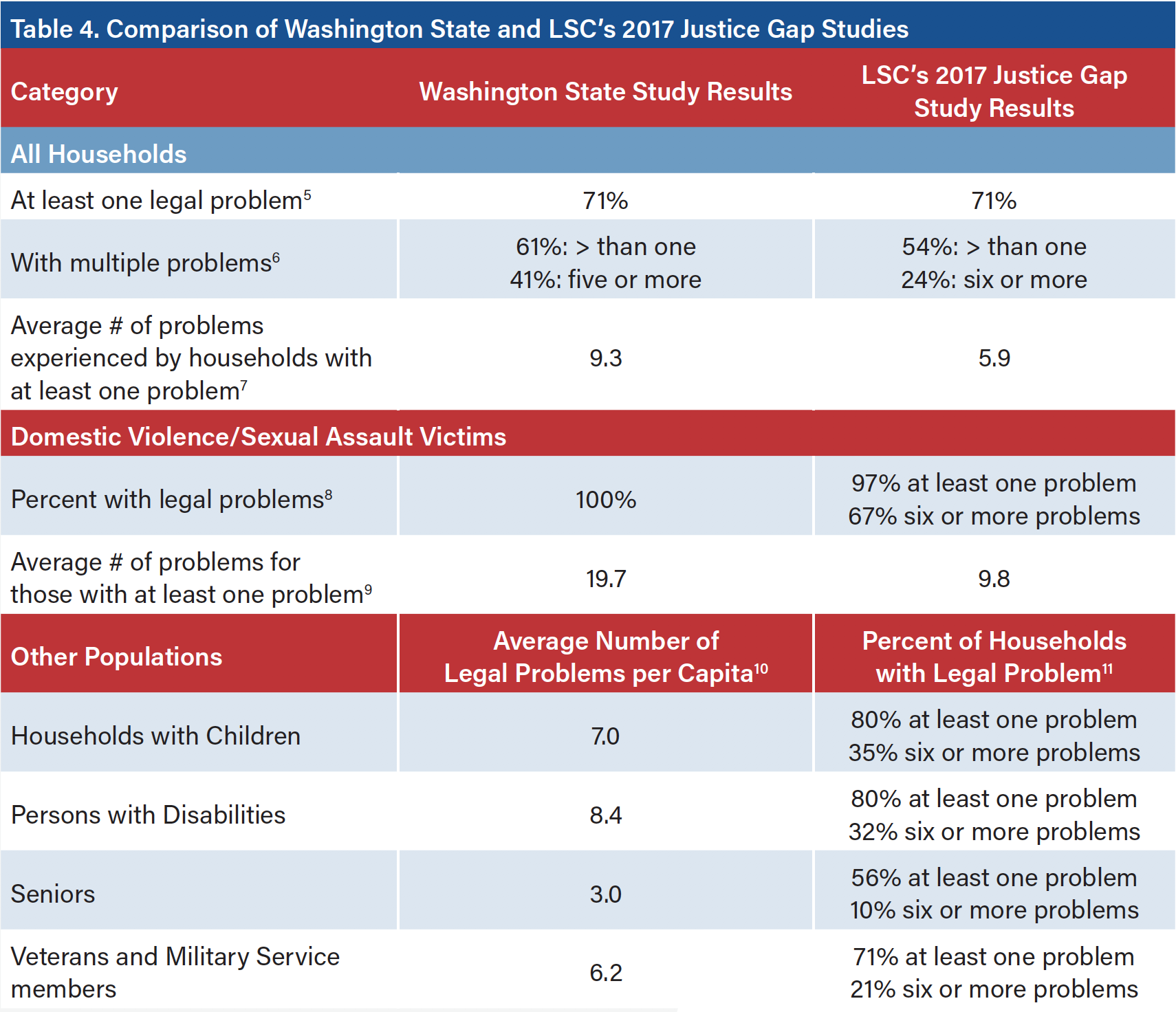

The Washington State Supreme Court recently commissioned a study to survey the civil legal needs of low-income persons in Washington. The study was conducted by the Social and Economic Sciences Research Center (SESRC) at Washington State University. The results of the Washington State study were similar to LSC’s Justice Gap report of 2017. As shown in Table 4 below, high percentages of low-income persons experienced civil legal problems in a year, and most experienced multiple civil legal problems. Like the findings in LSC’s Justice Gap Report, many individuals with civil legal problems in Washington State received no or inadequate legal assistance. The Washington State study found that 76% of all households received no assistance, while LSC’s Justice Gap study found low-income Americans received no or inadequate professional help for 86% of their civil legal problems.

The Washington State study also found high percentages of low-income persons could resolve some or all their legal problems when they had legal assistance. For example, for those who were able to get some level of assistance:

- 61% could solve some portion of their legal problems.

- Nearly one-fifth (18%) resolved the problem completely.

Unrepresented Litigants

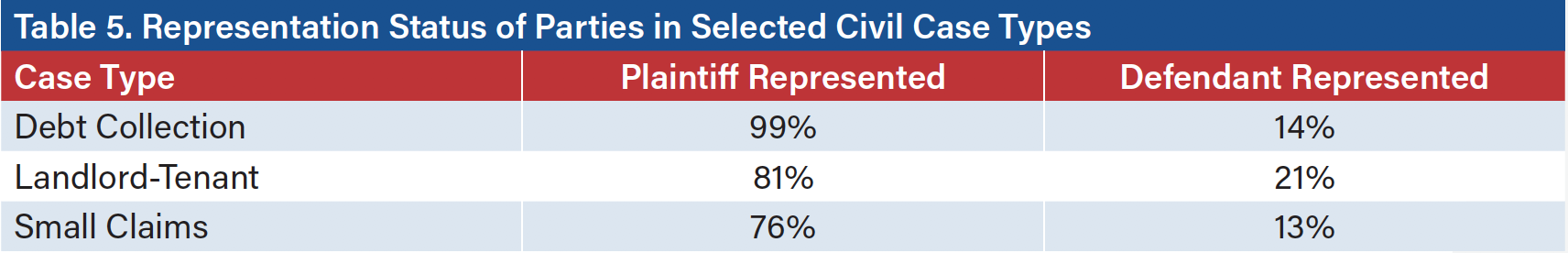

Every year, millions of Americans navigate the legal system without a lawyer. Inadequate funding for legal aid, combined with a large poverty population, has increased the number of unrepresented litigants in state courts. A national study by the National Center for State Courts found that the representational imbalance among plaintiffs and defendants has dramatically worsened over the last two decades: while plaintiffs represented by attorneys declined only slightly (from 99% to 96%), attorney representation for defendants fell by more than half (from 97% to 46%). The NCSC study found this imbalance is especially acute in financial and housing cases. As shown in Table 5, plaintiffs are seven times more likely to be represented than defendants in debt collection cases, six times more likely to be represented in small claims cases and four times more likely to be represented in eviction / landlord-tenant

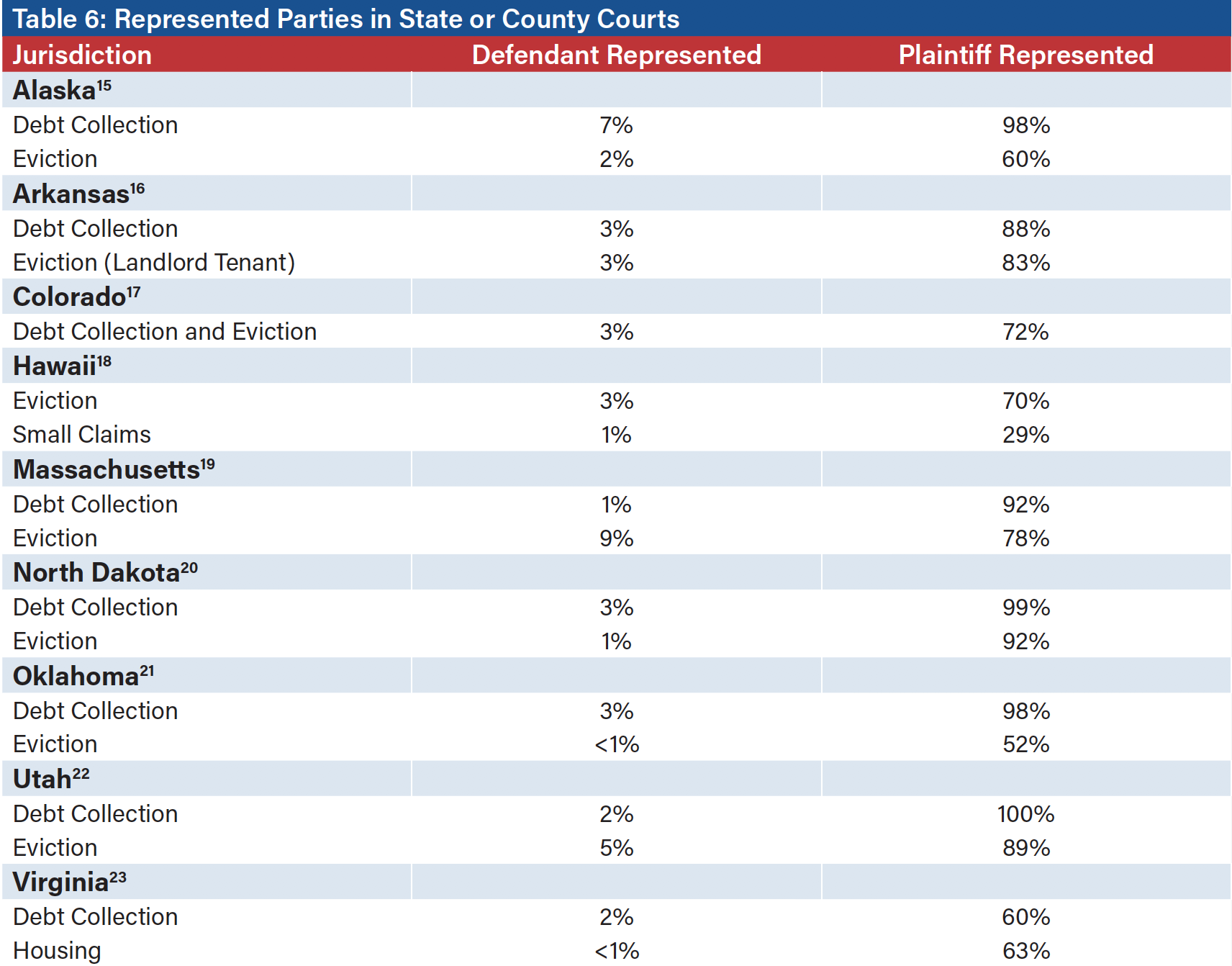

State studies also consistently show that the clear majority of civil legal cases include at least one unrepresented party. In some states and in some types of cases, as many as 80%-90% of litigants are unrepresented, even though their opponent has a lawyer. The traditional adversarial model where both parties have legal representation is not the norm.

Table 6 highlights a sample of states showing the percentage of represented parties in state courts in debt collection, eviction/landlord-tenant, and small claims cases.

Impact of Not Having a Lawyer

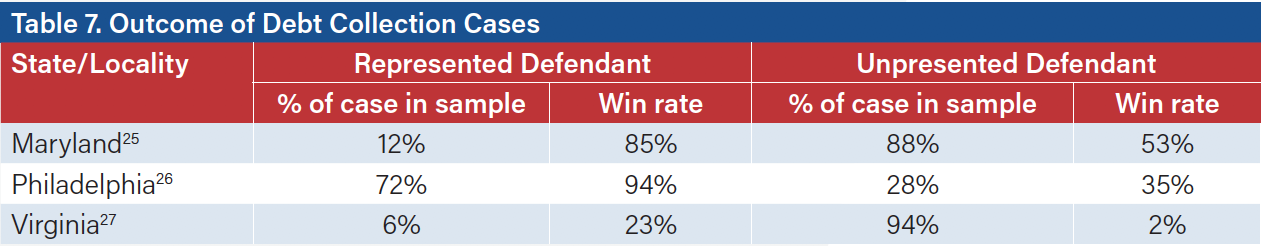

The large number of unrepresented litigants is compromising the ability of the courts to provide equal justice to low-income people. Numerous studies have shown that represented parties have substantially higher success rates than unrepresented parties. Vulnerable populations such as persons with mental disabilities, domestic violence survivors, and those with limited proficiency in English are especially disadvantaged.

Table 7 shows the outcome of debt collection cases where defendants are represented compared to unrepresented defendants in Virginia, Maryland, and Philadelphia. In Virginia, win rates for represented defendants are 10 times those of unrepresented defendants; in Philadelphia, they were nearly three times those of unrepresented defendants; and in Maryland, represented defendants were likely to prevail more than half as often as unrepresented defendants.

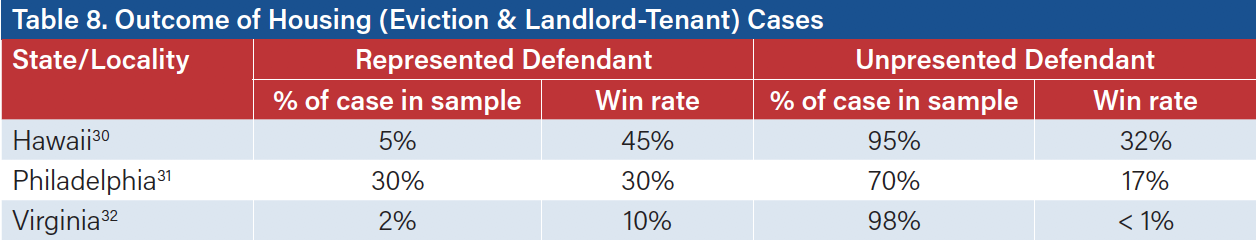

Recent studies have focused on low-income tenants facing evictions without an attorney. In many jurisdictions, reports show that nearly 90% of landlords are represented by counsel, while 90% of tenants are not. Having a lawyer increases the odds of being able to stay in one’s home. For example, a New York City study found that unrepresented were evicted in nearly 50% of cases while represented tenants were able to stay in their homes 90% of the time.

Table 8 highlights the outcome of housing cases for selected jurisdictions. In Virginia, represented defendants’ win rates are 20 times more than unrepresented defendants’ win rates. In Philadelphia, represented defendants are roughly twice as likely to prevail as unrepresented defendants, and in Hawaii they are also significantly more likely to prevail.

Impact of Unrepresented Litigants on the Court System

For the past several years, LSC has heard from judges across the country about the negative impact that the increasing number of unrepresented litigants has on the nation’s justice system. Large numbers of unrepresented litigants clog the courts, take up the time of court personnel, cost opposing parties more in legal fees because of disruptions and delays; cause more cases to advance to litigation, which means that fewer cases are settled, and result in cases being decided on technical errors rather than the legal merits.

The Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators detailed the consequences of lack of representation in their 2013 paper, “The Importance of Funding for the Legal Services Corporation from the Perspective of the Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators.” Highlights include:

- When an unrepresented litigant does not understand standard procedures and paperwork, judges must spend more time on the bench explaining information commonly understood by lawyers or eliciting facts that the party should have presented.

- Court clerks may have to answer more questions and provide additional assistance.

- More cases reach the courts as litigation (as opposed to being settled) when one or both parties are unrepresented.

- When one party in a case is represented by counsel and the other is not, delays and disruptions resulting from one party being unrepresented can increase the cost of counsel for the represented party.

Impact of LSC Funding on Grantee Services

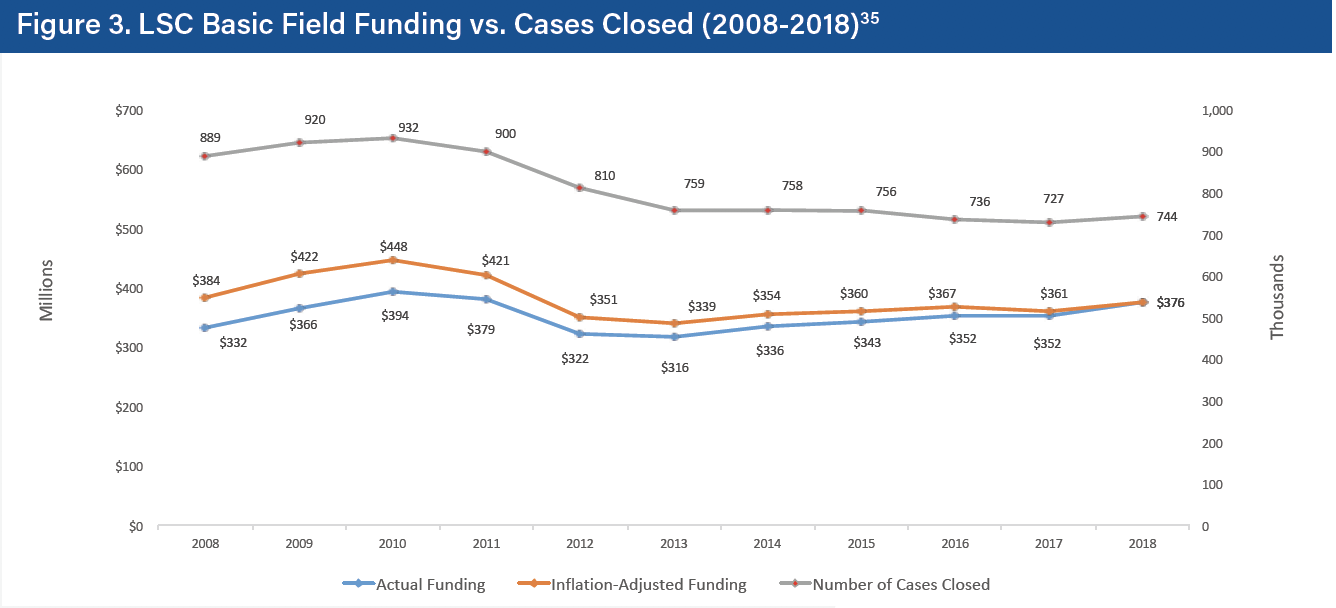

There is a clear correlation between the number of cases closed by LSC grantees and the funding appropriated by Congress. In 2018, LSC grantees closed a total of nearly 744,000 cases nationwide, an increase of nearly 17,000 cases, or 2.3%, from 2017. As illustrated in Figure 3, LSC’s basic field funding closely tracks the number of cases closed by LSC grantees. The chart includes both actual appropriations for LSC basic field grants and the inflation-adjusted (real) dollars for each year from 2008 to 2018.

When LSC’s basic field funding reached $394 million in 2010, the highest in LSC’s history in absolute terms before FY 2020, the total number of cases closed by LSC grantees also increased to 932,000. When LSC’s basic field funding dropped by 20% from 2010 to 2013, cases closed declined by nearly 19% for the same period (932,000 cases closed in 2010 dropped to 759,000 in 2013).

The relationship between basic field funding and case closures provides an important measure of the efficiency of the public investment in LSC as an organization and the provision of direct civil legal services to low-income households.

LSC Grantees Provide Other Valuable Services

Case closures alone do not present a complete picture of the range of services LSC grantees provide. Grantees provide extensive other services, including providing legal information and materials that enable low-income people to learn how to enforce important legal protections. These numbers provide a broader measure of the scope of LSC grantees’ reach into their local communities and the many people with whom grantees share informational resources.

Websites

In 2018, more than 11 million people visited grantee websites for information and assistance. These websites provide information about where to find legal help; court locations, procedures, and forms; and a wide range of self-help resources to identify and pursue appropriate legal remedies, including videos, classroom modules, fact sheets, and automated systems to generate and download ready-to-file court forms.

Legal Information Provided Directly To Low-Income People

Grantees provided legal information to an additional 1.46 million low-income people at other venues and events:

- 826,000 people at legal education clinics,

- 380,000 people at court help desks,

- 249,000 people on a one-on-one basis at legal education workshops.

The information provided at these venues helps low-income people better understand their legal rights. Court help desks can take many forms. Grantee staff and volunteers help individuals understand court procedures and navigate the process to represent themselves. They can also provide legal information to targeted populations. For example, at the request of the Maine Judicial Branch, Pine Tree Legal Assistance staff and volunteers conduct court-based “information sessions,” which provide homeowners with information about the foreclosure process.

Grantees often provide one-on-one legal information to low-income persons in tandem with group legal education clinics. At the conclusion of these events, grantees provide follow-up information to individuals on a one-on-one basis. After a grantee has identified areas of the broadest concern that can be easily explained in group settings, attorneys prepare a curriculum and self-help materials for use throughout the local community.

Outreach Events And Collaborations With Partners

Grantees also conducted over 10,000 outreach events for partner organizations, such as bar associations, other legal service providers, and social service agencies. For example, grantees participate in veteran’s “stand downs” or collaborate with their state’s Veterans Affairs offices and VA medical centers. Many grantees have medical-legal partnerships to educate health personnel about the types of legal problems that lawyers can help remedy.

Many grantees provide training to enhance partner organizations’ services to low-income persons. For example, over a nine-month period, a MidPenn Legal Services attorney provided training on landlord tenant law to justices in Pennsylvania’s Magisterial District Justice courts. Lakeshore Legal Aid in Michigan conducted a three-day training on enhancing judicial skills in domestic violence cases for the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. And Pine Tree Legal Assistance conducted 74 trainings for medical staff in Maine to increase community awareness and responses to the problem of lead paint poisoning that affects individuals living in the state’s old housing stock.

Some grantees convene conferences to educate larger groups. For example, Southwest Virginia Legal Aid Society (SWVLAS) sponsored a domestic and sexual violence conference attended by almost 200 professionals, including private attorneys, victim-witness agencies, shelter staff, court staff, prosecutors, and law enforcement. The conference was part of the program’s strategy that enabled them to develop more than 100 written agreements with agencies to provide comprehensive services to domestic violence survivors.

Referrals

LSC grantees made 590,000 referrals to non-legal entities and other legal services organizations or attorneys in 2018. These numbers highlight the relationship that LSC grantees have with other stakeholders in the community that serve low-income individuals.

The Value of Investing in Civil Legal Aid

A growing body of research demonstrates that investment in civil legal aid stimulates significant economic benefits for communities, state and local governments, and individuals. Studies in several states illustrate that civil legal aid positively affects the housing market, homeless shelter costs, foreclosure and eviction rates, and employment, and reduces the cost of domestic abuse. Examples of economic benefits from recent state studies include:

-

- Providing legal aid to survivors of domestic violence saved $2.9—$3.9 million in avoided costs.

- Providing legal aid saved $19.6 million in housing-related matters.

- Providing legal aid saved $14.8 million in costs associated with consumer finance issues.

-

- Providing legal aid saved the state $1.8 million in housing-related matters ($1.1 million in avoided foreclosure costs and $700,000 by preventing evictions).

- Providing legal aid to survivors of domestic violence saved $800,000 in emergency medical treatments and law enforcement costs.

- Providing legal aid saved the state $1.8 million in housing-related matters ($1.1 million in avoided foreclosure costs and $700,000 by preventing evictions).

-

- Providing legal aid saved $7.52 million in health insurance payments and avoided healthcare charges.

- Providing legal aid saved $1.46 million by preventing homelessness, evictions, and foreclosures.

-

- Providing legal aid saved the state $63.7 million in housing, family/juvenile costs, and education.

- Assisting survivors of domestic violence saved the state $9.5 million.

-

Providing civil legal aid saved the state $594.5 million:

- $555.8 million in avoided emergency shelter costs.

- $28.1 million in avoided foreclosure costs.

- $10.6 million in avoided costs associated with domestic violence.

-

Providing civil legal aid saved the state $38 million:

- $18 million in cost savings for unnecessary medical treatments by end-of-life medical directives.

- $12.4 million in avoided foreclosure costs.

- $4.2 million in avoided costs associated with domestic violence.

- $3.6 million in avoided emergency shelter costs.

-

Providing civil legal aid saved the state $60.4 million:

- $2.9 million in avoided costs of emergency shelter for low-income families.

- $50.6 million in avoided foreclosure costs.

- $6.9 million in avoided costs associated with domestic violence.

-

- Providing legal aid to survivors of domestic violence saved $11.57 million in avoided costs.

- Providing legal aid saved approximately $3.6 million in housing matters, including evictions and foreclosures.

-

- Providing legal aid saved the state more than $1 million by preventing foreclosures.

- Providing legal aid saved the state nearly $1.5 million in costs associated with domestic violence, child custody, and support.

-

- Assisting homeowners avoid foreclosures and evictions saved the state $2.6 million in emergency shelter costs.

- Providing legal aid to survivors of domestic violence saved the state more than $300,000.

-

- For every $1 spent representing families and individuals in housing court, the state saved $2.69 on other services, such as emergency shelter, health care, foster care, and law enforcement.

- Providing legal aid to survivors of domestic violence saved the state $16 million.

-

- Providing legal aid to survivors of domestic violence saved the state $7.3 million.

- Assisting homeowners avoid foreclosures and evictions saved $4.1 million in shelter costs.