Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies, Committee on Appropriations, by James Sandman

Chairman Wolf, Congressman Fattah and Members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to discuss the Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Request of the Legal Services Corporation.

For more than three decades, the Legal Services Corporation (LSC) has touched the lives of millions of low-income Americans, addressing the civil legal needs of the elderly, victims of domestic violence, veterans seeking the benefits to which they are entitled, disabled individuals, tenants facing unlawful evictions, and other poor Americans. Every day at LSC-funded programs, legal aid attorneys and volunteer lawyers help families facing foreclosure and individuals who have lost jobs and find themselves slipping into bankruptcy or entangled in other serious legal problems. Today, LSC is the single largest funder of civil legal services—the most important part of the nation’s strained and stressed legal aid network. Requests for assistance are increasing; the poverty population is growing. Funding from non-federal sources is decreasing.

The United States has the greatest legal system in the world, and our country’s commitment to the rule of law is second to none. Because of the bipartisan Congressional support for LSC, our nation has created a public-private partnership focused on fulfilling America’s pledge of equal justice for all regardless of income. LSC is at the center of the nation’s access to justice efforts, and the support of this Subcommittee and this Congress is critically important—particularly now, as a larger number of low-income Americans than ever before qualify for legal services.

It is a great privilege for me to serve as LSC’s president and chief executive. I joined the Corporation at the end of January, after having spent most of my career in the private sector, where I had significant management experience. I worked for 30 years at the law firm of Arnold & Porter LLP, including 10 years as Managing Partner. In 2007, I decided to go into public service, and I became General Counsel of the District of Columbia Public Schools shortly after Michelle Rhee became Chancellor. I served as president of the District of Columbia Bar in 2006-2007, and I am now the chair of the D.C. Bar’s Pro Bono Committee. I am currently the co-chair of the District of Columbia Circuit Judicial Conference Committee on Pro Bono Legal Services and a member of the Pro Bono Institute’s Law Firm Pro Bono Project Advisory Committee. I also have served on the board of the Neighborhood Legal Services Program in the District of Columbia.

Robert J. Grey, Jr., of Richmond, Virginia, a member of the LSC Board of Directors, joins me here today. He is a distinguished lawyer and a past president of the American Bar Association. He chairs the LSC Board’s Finance Committee and co-chairs the Board’s Special Task Force on Fiscal Oversight. He also has tremendous experience in recruiting lawyers and firms for pro bono activities and will bring the Subcommittee up to date on that aspect of our work.

My goals as President of LSC are to increase resources and funding for civil legal services; to maximize the efficiency, effectiveness, and quality of LSC and the 136 nonprofit legal aid programs that receive LSC grants; to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship within LSC and among the programs that LSC funds; and to further improve collaborations with judges, state Access to Justice Commissions, the organized bar, private attorneys, foundations, law schools, and others involved in serving the needs of low-income Americans.

Equal Access to Justice

In founding LSC, Congress entrusted the Corporation with a dual mission: to provide equal access to justice and to ensure the delivery of high-quality civil legal assistance to those who would be otherwise unable to afford counsel.

Equal access to justice is essential in our democracy, and LSC has become the bedrock on which our national system of access to civil justice now stands. The system is supported today by state and local appropriations, Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts (IOLTA) funds, court filing-fee surcharges, foundation support, and private contributions—but those funding sources have been hit hard by the recession. LSC funding has been the most reliable source of legal aid funding in the past few years. All of these resources are augmented by the volunteer hours of pro bono attorneys.

The Conference of Chief Justices, the highest judicial officers in the 50 states and territories, recognized the importance of LSC’s role in a February resolution of support. “In recent years,” the resolution says, “many states have invested substantially in the core civil legal aid infrastructure funded through the federal Legal Services Corporation, and [a] reduction and/or withdrawal of federal funding would fundamentally undermine the vitality and effectiveness of state-based legal aid delivery systems and adversely affect civil judicial operations.”

LSC funding helps “to provide a stable financial base for the [legal services] providers, leverages other resources, enables program planning and avoids budget fluctuations that can disrupt staffing and services,” the New Mexico Commission on Access to Justice said this year. “The positive outcomes those legal aid agencies achieve for clients not only help our poverty population, but also impact our communities’ abilities to remain strong and vibrant,” the Commission said.

The access to justice umbrella brings together the judiciary, bar associations, legal aid providers, law schools, private attorneys, business and civic organizations, and other parties to address the civil legal needs of low-income individuals. Twenty-four states have established Access to Justice Commissions, and many other states have similar entities to achieve access to justice goals. The majority of the Commissions have been created in the last five years.

These access to justice initiatives foster partnerships and collaborations among key segments of the legal profession. In New York, for example, where almost two-thirds of homeowners at foreclosure settlement conferences appear without an attorney, the state’s chief judge, Jonathan Lippman, set up a pilot program this year to provide low-income homeowners with legal assistance at the settlement conferences. As a part of the pilot, Legal Services of the Hudson Valley, funded by LSC, will assign attorneys to work at courthouses. The Hudson Valley program also will work with at least two bar associations and private law firms to recruit approximately 50 pro bono attorneys for the project.

We all agree that the rule of law is in jeopardy when the protections of the law are not available to increasingly large numbers of low-income citizens—especially children, the elderly and victims of domestic abuse. Writing in 2009 in Wyoming Lawyer, the state bar magazine, about equal access issues, state District Court Judge Scott W. Skavdahl said the best interests of children are often lost in disputes involving unrepresented litigants. “The victims in these cases are wholly innocent and the errors of an uninformed decision can be untreatable and the harm irreparable. . . . Access to justice affects more than just pro se litigants. It impacts the quality of a judge’s decision, how our legal system is perceived and the lives of people.”

Challenges and Accomplishments

In 2009, nearly 57 million Americans, the largest number since LSC was established, were eligible for civil legal assistance from LSC programs. Almost 20 million of them were children. We estimate that the number qualifying for assistance has now grown to more than 63 million, and that an estimated 22 million of this total are children. Since 2008, the eligible population has increased by more than 17 percent. And these are the poorest of the poor. To qualify for services at LSC-funded programs, a client cannot have more than $27,938 in income for a family of four.

LSC’s own data reflect the impact of the economic downturn. LSC-funded programs tell us they are receiving increased requests for legal services in areas related to the economy, such as foreclosure and unemployment.

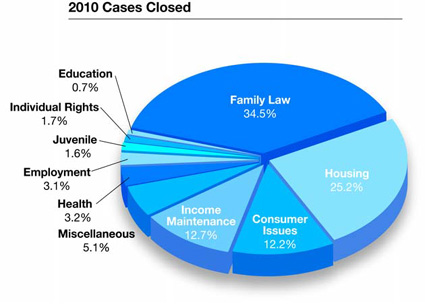

Last year, LSC-funded programs closed 932,406 cases, up from 920,447 in 2009. In 2010:

- Foreclosure cases were up 20 percent, to 23,984.

- Unemployment cases increased 10.5 percent, to 27,384.

- Landlord-tenant disputes rose by 7.7 percent, to 131,543.

- Bankruptcy, debt relief (39,346) and consumer finance cases (7,011) were up by nearly 5 percent.

- Domestic violence cases increased by 5 percent, to 48,957.

The following chart shows the major categories of the 932,406 cases:

LSC programs are involved in an array of cases, based on priorities set by their local boards of directors. Let me highlight one area—foreclosure—because over the last three years LSC-funded programs have reported significant increases in cases involving foreclosure.

Almost all LSC programs now report handling foreclosure cases, and more than 40 LSC programs have established foreclosure units. LSC programs that are well known for their foreclosure work include Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, Legal Services of Greater Miami, Legal Aid Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago, Indiana Legal Services, Iowa Legal Services, Legal Services NYC and the LSC programs in western and eastern Missouri. Foreclosure work is often complex and labor-intensive.

Atlanta Legal Aid’s work has helped protect homeowners from predatory lenders—those who make unsolicited loans with exorbitant interest rates to low-income homeowners who did not understand what they were committing to and have no way of making the payments. Last year, a pro bono attorney for Pine Tree Legal Assistance, the LSC program in Maine, was at the center of a major court ruling. The court determined that the practice of multiple foreclosure filings without sufficient documentation of the title and often with inaccurate affidavits—the so-called “robo-signing” phenomenon—was not acceptable. The decision eventually led banks to suspend foreclosure filings in 23 states.

Several legal aid programs provide housing counseling to homeowners who seek it; others work with housing counselors to advise them when to refer homeowners to lawyers to review their problems. West Tennessee Legal Services, an LSC program, sponsors several counseling projects through NeighborWorks America, the congressionally-chartered nonprofit organization dedicated to improving distressed communities.

LSC programs, such as those in Maine, Nevada and Florida, have participated on state Supreme Court commissions that led to the establishment of mediation programs for foreclosures. Mediation is a particularly helpful tool for the representation of those who started on loan mediators often require the full participation of lenders.

Cases involving bankruptcy and consumer matters, such as complaints about fraud and disputes over debt-collection practices, also have increased during the last three years. Legal Services of Alabama, Georgia Legal Services, Maryland Legal Aid Bureau, and Montana Legal Services are among the LSC programs that report handling more consumer and bankruptcy cases. To address consumer issues, Colorado Legal Services created a Consumer Unit in its Denver office. The Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles has added a monthly clinic to its regular intake and a hotline to address an overflow of requests for assistance on consumer issues, and partnered with a law school in September 2010 to start a bankruptcy clinic.

LSC encourages legal aid programs to pursue new initiatives that expand access to justice. Last November, Pine Tree Legal Assistance in Maine launched StatesideLegal.org, the first website in the nation to focus exclusively on federal legal rights and resources important to our veterans. LSC also has started an awareness and training campaign to create referrals between legal aid offices and the Department of Veterans Affairs Readjustment Counseling Service offices, known as Vet Centers, across the nation. This initiative is moving in phases, and LSC programs are reaching out to Vet Centers in large states, such as California, Texas, New York and Florida.

Behind these initiatives and the caseload numbers are people in often unique circumstances who never imagined they would need but could not afford the assistance of a lawyer in order to get back on their feet or to start a new life. Here are some case summaries from LSC programs:

- A Texas couple signed loan documents to fix their dilapidated house, but with very little understanding of what they signed. The husband died, and his 58-year-old disabled widow kept up the loan payments until she had a heart attack. Her medical expenses did not leave enough to make her home loan payments. Lone Star Legal Aid negotiated a settlement to prevent foreclosure, allowing this person with a severe heart condition to be cared for in the comfort of her home.

- A disabled veteran was wrongly accused of damaging an apartment. Maryland Legal Aid defended the veteran and discovered other tenants also were victims of fraudulent activities that have led to a state investigation.

- A husband tried to kill his wife and their daughter by setting the house on fire. When his wife ran from him, he found her and smashed her head with a gun, causing serious brain injury. Legal Aid of Western Missouri enrolled her in the state’s protection program, and helped her get a divorce and sole custody of her daughter.

- An Alabama woman lived on food stamps and Social Security and fell behind on her mortgage payments when she had to pay a repair bill for a bathtub that fell through the floor. She almost lost her home, but Legal Services Alabama helped her renegotiate a loan modification with the Veterans Affairs Department.

- A 73-year-old Maryland woman was duped by a debt-settlement company into signing a contract with exorbitant administrative fees and authorizing automatic monthly debits from her bank account. The company left some of her debts unpaid, snarling her in litigation. Maryland Legal Aid got the contract canceled and $1,000 in settlement money.

I am trying to meet as many leaders of LSC-funded programs as quickly as I can, as you might expect. My first impression is that these programs are lean, stretched to the limit, and unable to come close to meeting the demands for their services. Recent research by the National Association for Law Placement shows that civil legal aid lawyers are the lowest paid members of the legal profession, earning less than public defenders and other public interest lawyers. First- year staff attorneys in LSC programs earn an average of $43,000 a year and can expect to earn about $59,000 a year after 10-to-14 years of experience. We hear increasing reports of programs that are reducing or eliminating employee benefits.

I have also been reminded that these staff attorneys are engaged in emotionally demanding work. At a briefing at the Maryland Legal Aid Bureau, the intake coordinator told me she now interviews people who never could have imagined the financial circumstances in which they now find themselves and who never thought they would need the help of a legal aid attorney to get back on their feet. The people she interviews are often in tears when explaining what brought them to the doors of the Maryland program.

The Maryland intake coordinator recently saw a couple, in their late 30s, who have two children in elementary school. “Stephen” worked for a supermarket, making between $45,000 and $50,000 a year. His wife, “Marilyn,” has her own in-home day care business, earning about $20,000. Their problems began when Stephen was laid off, about the time the couple faced a balloon payment on their mortgage. With Marilyn as the sole breadwinner, they fell behind on their payments, and the bank threatened foreclosure.

Maryland Legal Aid sent the couple to housing counselors for a loan modification, but their finances do not look favorable for that option. Stephen and Marilyn had gotten into a mortgage with payments set to go up every year, without understanding what they were signing and what they were doing. If they go into foreclosure, Maryland Legal Aid will probably represent them in mediation and try to find some options that work for all parties.

Unfortunately, LSC programs are seeing a lot more people like this couple—people who are having trouble finding jobs, spending too much time out of the workforce, and encountering legal problems.

As the Subcommittee knows, large-scale, survey-based studies conducted in 15 states during the last decade have found that only a fraction of the legal problems experienced by low-income people are addressed with the assistance of a private or legal aid lawyer.

Our nation needs federal support to maintain our commitment to equal access to justice. LSC serves as the primary conduit for supporting a national network of civil legal aid providers that help our nation meet its pledge of equal justice for all.

Fiscal Year 2012 Request

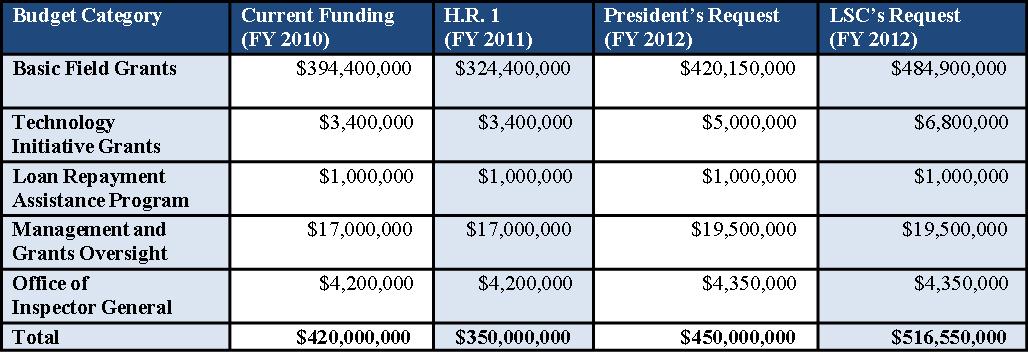

For Fiscal Year 2012, the LSC Board of Directors approved a resolution requesting $516,550,000, which includes $484,900,000 for basic field grants (approximately 94 percent of the overall budget request).

The Board’s request seeks the same level of funding for FY 2012 as requested in FY 2011. The Board weighed several factors in making the request, including the fiscal pressures facing the nation; the needs of LSC clients who seek legal assistance with foreclosures, unemployment compensation, and a myriad of other matters; and the increase in the population eligible for LSC- funded services.

This may be the point to address an obvious question: in the current fiscal environment, why is LSC asking for more funding than it currently receives? The question we have asked ourselves is, given the growing need in our society, and our statutory charge, how can we not ask for more resources? How can we not ask for funding to ensure that the playing field is even?

The Board, concerned about the increase in the number of people living in poverty and their growing need for civil legal services, decided it would not retreat on funding and, instead, froze the request at the level requested for Fiscal 2011. President Obama made a different decision, but still believed LSC should receive a funding increase.

Funds provided to LSC programs help communities avert more costly interventions. When a family escapes domestic violence, we save on the costs of medical care for injured victims and the follow-up counseling for affected children. When LSC programs resolve landlord-tenant disputes, we keep families together and avoid homelessness and emergency shelter costs. When LSC-funded technology initiatives create automated, standard legal forms, we save time for lawyers and for courts. When we provide legal aid at an early stage, we can avoid litigation and the adverse impact on communities and governments. For individuals, legal aid can be a path to self-sufficiency and stability.

Significant parts of the non-federal funding structure have been essentially flat or declining over the last three years. An important source of non-federal funding for LSC programs, Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts (IOLTA), has declined from 12.7 percent of total funding in 2008 to 7.1 percent of total funding in 2010. State and local grants and United Way contributions also have declined. Numerous local legal aid programs are very concerned about their funding from non-LSC sources over the next two years, making federal support increasingly important as more Americans are at risk of being left behind by the slow economic recovery and find themselves confronting serious legal problems.

The following chart shows LSC’s current funding, at FY 2010 levels; H.R. 1 funding levels; President Obama’s FY 2012 request, and the LSC Board’s FY 2012 budget request:

In addition to recommending increased funding for basic field grants, LSC also requests:

- $6,800,000 for Technology Initiative Grants (TIG). With this funding, TIG would strengthen and expand the technology infrastructures of legal aid programs, expand wireless broadband access to provide cost-effective legal services in rural areas, and expand assistance for unrepresented litigants through the development of additional automated forms. Increased wireless broadband access would allow legal aid attorneys to hold more clinics in rural areas and provide intake services to low-income citizens. Because many courts have experienced an increase in the self-represented, and because court procedures vary and may be difficult to understand, TIG provides LSC with an ongoing opportunity to work with clients on standard court forms that hold the potential to save time for legal aid attorneys and to increase access for the self-represented. In response to the needs of the self-represented, legal aid programs and libraries are developing partnership strategies and specialized tools to serve library patrons seeking legal help.

- $1,000,000 for the Corporation’s Herbert S. Garten Loan Repayment Assistance Program (LRAP). LSC programs have found that helping lawyers reduce their student debt substantially increases the likelihood that they will stay with their programs. It also makes it easier for programs to recruit new attorneys.

- $19,500,000 for Management and Grants Oversight (MGO). The proposed increase would expand LSC’s grants oversight operations, including a training program for grantee board members and grantee staff in order to improve local board governance, fiscal oversight and other aspects of grantee operations. The proposed increase also would better enable LSC to further strengthen internal controls for grants administration.

- $4,350,000 for the LSC Office of Inspector General. The OIG request is included in the LSC total, but is made separately by the Inspector General through the LSC Board of Directors.

The proposed MGO training initiative would set aside about $450,000 to create and support a training unit to develop web-based and in-house training for LSC-funded programs. The training would:

- Expand grantee board member training and dissemination of best practices on board governance and oversight in order to support better prepared grantee board members who can conduct more sophisticated oversight of their programs.

- Expand grantee staff and board training on fiscal oversight and management best practices to produce better internal controls and more effective management.

- Expand grantee staff and board training on LSC regulatory compliance requirements.

- Provide assistance on managing pro bono and private attorney involvement, leadership mentoring, technology, and program development.

Improving Management

LSC continues to find ways to conduct its business more efficiently and effectively, and I am committed to further improvements in the operations and the management of the Corporation. In my first weeks as LSC President, I have addressed an all-staff meeting and have met individually or greeted almost all of the LSC employees. I believe the tone at the top is important, and I do my best to foster a culture of integrity, accountability, cost-consciousness, and commitment to high standards of quality. I am acutely aware that we at LSC are stewards of public funds, and I will run a tight ship. I conduct weekly management meetings to hear from office directors. I have an open-door policy for all employees, so that any member of the staff can bring issues to my personal attention; a number of employees have already come to talk to me. I meet regularly with representatives of our employees’ union, and am committed to constructive and harmonious labor-management relations. I believe that managing people well is critical to the success of any enterprise.

I hope to bring LSC to a new level of excellence, to reach out and listen to all interested parties, and to continue growing this great public-private partnership that strives to provide access to justice to so many Americans.

Congress has provided us with outside expertise on management issues—the Government Accountability Office (GAO). LSC has found great value in GAO’s reviews in recent years, and LSC has accepted all of the recommendations made by GAO. Robert Grey will discuss our progress in this area in his testimony.

I also want the Subcommittee to know that I regard the LSC Inspector General as a colleague with whom I share a common mission—improving efficiency and effectiveness and deterring waste, fraud and abuse. I meet with Inspector General Jeffrey E. Schanz every other week in his office, and I have solicited his advice on systemic changes that he thinks might be appropriate to avoid recurrences of problems LSC has experienced in the past. I am grateful for his help and his graciousness in welcoming me to LSC. I value our relationship and look forward to working with him for the betterment of LSC.

Going Forward

The Constitution calls for establishing justice as a national purpose in its very first line. Our Pledge of Allegiance proclaims our commitment to “justice for all.” “Equal Justice Under Law” is engraved over the entrance to the U.S. Supreme Court building.

With the additional funding provided by the Congress in recent years, LSC-funded programs have been able to help millions of Americans. While we hope that the recession is behind us, unemployment remains high, suggesting that many more low-income Americans will be coming to LSC programs for assistance with legal matters.

But the progress we have made will be threatened if access to justice is limited. The support of Congress is critically important as low-income Americans struggle in this economy. For FY 2012, we urge the Subcommittee to help us close the justice gap by approving the LSC Board’s request for $516,550,000. With the Subcommittee’s support, we can narrow the justice gap, reaffirm our national commitment to the rule of law, and bring self-sufficiency and stability to individuals and families across our country.

Thank you very much.